Chapter 8 Hyponatraemia

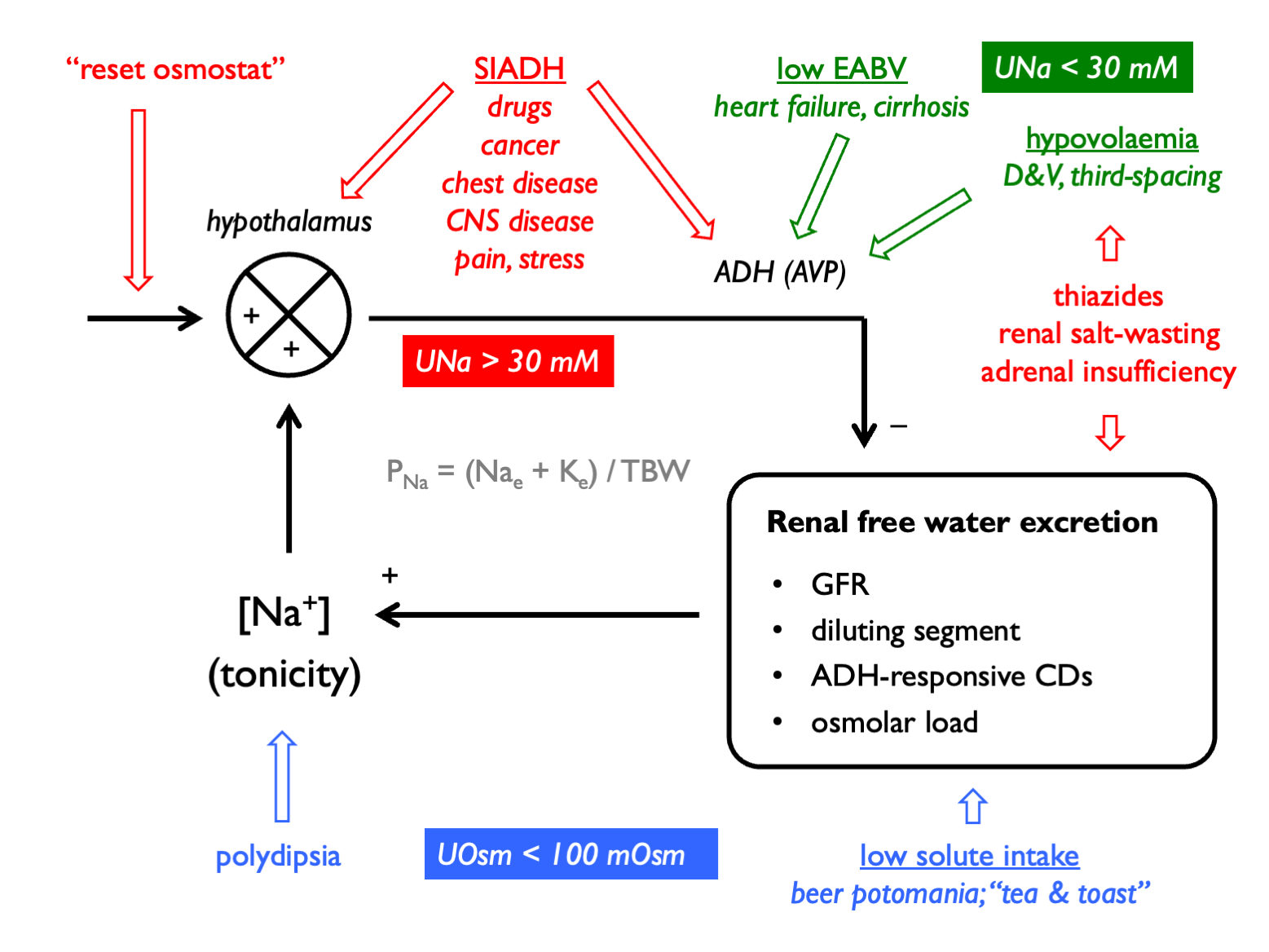

Hyponatraemia is caused by free water excess. When this is associated with reduced plasma tonicity, this can cause cerebral oedema.

The general approach to diagnosis is as follows:

Order of operations in hyponatraemia:

- confirm true hypotonic hyponatraemia

- correct for [glucose] in hyperglycaemia

- check POsm

- determine clinical volume status

- check UOsm (< 100 mM suggests urine water excretion limited by low solute load or driven by XS water intake - i.e. hypothalamic-ADH-kidney axis intact)

- check UNa (< 30 mM suggests low effective arterial blood volume)

And remember to consider:

- is there total body K depletion?

- is solute intake low?

- check UK or calculate free water clearance to guide therapy

- calculate FEurate in tricky cases

The causes of hyponatraemia can be classified by volume status, UOsm and UNa:

8.1 Drug causes of hyponatraemia

| Mechanism | Drugs |

| Impaired urinary dilution | thiazide diuretics |

| Renal salt wasting | NSAIDs / antibiotics / PPIs (if AIN) |

| SIADH | antidepressants (SSRIs, TCAs) |

| antipsychotics | |

| anticonvulsants (esp. carbemazepine) | |

| anti-cancer (vinscritine, cisplatin…) | |

| opioids | |

| MDMA | |

| Reset osmostat | venlafaxine |

| carbamazepine | |

| Excessive thirst | MDMA |

8.2 Correction for hyperglycaemia

Hyponatraemia can result from an influx of water into the vascular (and interstitial) space in presence of an abnormaly high concentration of a plasma osmole. The commonest such clinical scenario is that of hyperglycaemia. (Hyponatraemia in this context is not dangerous per se because plasma tonicity is maintained near normal by glucose, an effective osmole.)

The value that PNa will correct to with resolution of hyperglycaemia can be estimated:

NB alternatively this can calculated by adding 0.4 mM to measured PNa for every 1 mM rise in Pglucose. The correction factor for haemodialysis patients is lower (0.27 mM for every 1 mM glucose) (Penne et al., 2010).

8.3 Urine sodium

In the steady-state, urinary sodium excretion will reflect sodium intake. On a normal Western diet, daily NaCl intake might be ~9g (=154 mmoles) (Campbell et al., 2015). If this were excreted in 2L or urine, then UNa would be ~ 77mM.

When volume homeostasis is threatened and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system is activated, renal sodium reabsorption is stimulated and UNa drops. As a rule-of-thumb, UNa is < 30 mM in volume depletion:

This threshold was derived in an elegant study of patients with hyponatraemia in which bona fide volume depletion was determined retrospectively by a positive response to a crystalloid bolus (Chung et al., 1987). It is more accurate to say that low UNa refects low effective arterial blood volume (EABV) rather than volume depletion per se). This hypothetical concept encompasses both intravascular volume and vascular tone, and is useful in explaining why the RAAS is activated in hypervolaemic (but low-perfusion) states such as heart failure and cirrhosis.

UNa will not accurately report EABV in the presence of any drug or disease that perturbs renal sodium excretion, such as:

- diuretics

- ATN

- salt-wasting nephropathies (Addison’s, Barrter, Gitelman)

- bicarbonaturia (look for low UCl)

- glycosuria

8.3.1 FENa

Urine sodium levels can be expressed as a fractional excretion.

Historically, FENa was used in an attempt to discriminate between an appropriate response to volume depletion in “pre-renal” AKI (FENa < 1%) and in-appropriate salt wasting in ATN (FENa > 3%). However, the sensitivity and specificity of FENa in this context are poor (Pahwa & Sperati, 2016). (FEurea can be used in a similar way and is less sensitive to error in patients who are treated with diuretics; FEurea < 35% is compatible with pre-renal AKI.)

FENa may be more useful in identifying patients exhibiting hepato-renal physiology (in which FENa << 1% and UNa < 10 mM).

8.3.2 FEurate as an alternative index of volume status

Urate transport in PCT is coupled to sodium transport (Kahn, 1989). Volume depletion will stimulate Na reabsorption in PCT and hence also urate reabsorption.

Interpretation(Maesaka et al., 2014; Choi et al., 2018):

- in normal subjects, FEurate is 4 – 11%

- in volume depletion (or states of low EABV), FEurate is low (< 4%)

- in volume expansion, SiADH or renal salt wasting, FEurate is high (> 11%)

8.4 Free water clearance

8.4.1 Calculating free water clearance

The quantitative contribution of the kidney to water homeostasis can be determined by calculating the osmolar- or electrolyte-free water clearance.

A dilute urine can be thought of as comprising a volume of urine that is isotonic with plasma PLUS a volume of “free” water. A concentrated urine can be thought of as a volume of isotonic urine MINUS a volume of “free” water. Free water clearance is a hypothetical concept that determines this volume of “free” water in the urine.

Traditionally, this was calculated by first determinine the total clearance of osmoles and subtracting this from urine flow:

However, as not all urinary osmoles are effective osmoles with respect to cell membranes, it makes more sense to determine the clearance of water that is free from only effective osmoles when working out how renal water clearance is likely to affect PNa. Therefore, it is usually preferable to calculate electrolyte-free water clearance (Nguyen & Kurtz, 2006). This approach was originally advocated by Goldberg, 1981 and then elaborated on by Rose, 1986:

Other effective osmoles (OEOs) may be: glucose, mannitol…

Most of the time, this can be simplified by considering only the dominiant urinary cations, sodium and potassium - or even further by calculating the urine:plasma electrolyte ratio, as proposed by Furst, 2000:

8.4.2 Clinical utility of free water clearance

The main clinical application of free water clearance is in determinine the quantitative contribution of the kidneys to the pathogenesis of hyponatraemia. This can help if diagnosing the cause of hyponatraemia and in guiding rational therapy.

Hyponatraemia will ensue when free water intake exceed free water clearance. A low free water clearance, in the context of hyponatraemia, indicates some sort of problem with the ADH-kidney axis.

Free water clearance can be used to determine the extent to which water intake should be restricted (in cases of euvolaemia or volume-expanded hyponatraemia where this should help to correct hyponatraemia). A meticulous approach entails calculating and using this to set a value for the daily water intake that would result in hyponatraemia - accounting for any insensible water losses and obligate free water intake.

A more straightforward approach - and one that can be followed when urine flow rate has not been documented - is to approximate from the urine:plasma electrolyte ratio (8.9) - sometimes known as the “Furst ratio” (Furst et al., 2000). The Furst formula makes various assumptions about body size, cation intake and insensible water losses in order to give a very approximate estimate of urinary free water excretion.

The estimates for net free water loss (and the restriction on water intake that would be required to raise plasma sodium) are as follows, with the duration being that required for 1L of urine output:

| U:P electrolyte ratio | estimated net free water loss | max fluid intake |

|---|---|---|

| >1.0 | 800 ml | 0 ml |

| 0.5 – 1.0 | 800 - 1300 ml | 500 ml |

| <0.5 | 1300 - 1800 ml | 1000 ml |

Based on this, a popular approximate guide to fluid restriction is:

| U:P electrolytes | set fluid restriction to… |

|---|---|

| UNa + UK > PNa | 500 ml (and give furosemide +/- supplemental NaCl) |

| UNa + UK ~ PNa | 500 - 800 ml |

| UNa + UK < PNa | >1000 ml |

EFWC can also be monitored serially in hypoNa to determine whether the patient is getting better or not. Ideally use short timed collections (e.g. 4 hrs) so can include urine volume. Can run urine through an ABG machine to get immediate electrolyte content.

8.4.3 Urine flow rate in hyponatraemia

Patients with hypovolaemic hyponatraemia are at particular risk of “over-correction” - i.e. a rapid rise in PNa that might precipitate osmotic demyelination. This is because after the initial phases of volume resuscitation, the volume stimulus to ADH secretion is removed and there is then a profound osmotic stimulus suppressing ADH production.

The first clinical sign that over-correction is imminent is a rise in urine output. But how much urine is too much urine? Using some complicated mathematics and reasonable assumptions, Buchkremer et al. used the Edelman equation to derive an estimate for this:

…up to a maximum of 100 ml per hr

8.5 SIAD

8.5.1 Diagnosis

Diagnostic criteria:

- POsm < 275 mOsm

- UOsm > 100 mOsm

- euvolaemic

- UNa > 30 mM (in normal salt and aq intake)

- absence of adrenal insufficiency, severe hypothyroidism, advanced CKD, diuretics…

Therefore must do a short-synACTHen test before diagnosing SIAD.

Supplemental criteria:

- Purate < 0.24 mM

- Purea < 3.6 mM

- FENa > 0.5%

- FEurea > 55%

- FEurate > 12%

Investigations once SIAD confirmed (Warren et al., 2023):

- drug chart review

- thorough history and examination (chest and CNS disease, cancer, infection, pain, stress…)

- CXR +/- CT thorax (in most)

- CT head and sinuses (in most)

- CT abdo/pelvis (less often)

- FDG-PET, DOTATE-PET (rarely)

The list of drugs that can cause hypotonic hyponatraemia is very extensive; the table above is far from comprehensive. See here for more complete list. Don’t be caught out by missing:

- tramadol, NSAIDs, opiods

- nicotine

- amiodarone

- PPIs

- ACEi (although unusual)

- methotrexate…

Neuroendocrine tumours - classically olfactory neuroblastomas - can cause SIAD for years before the tumour declares itself. Therefore CT of nasal sinuses an important part of the work-up, particularly in younger patients. DOTATATE-PET has been used to diagnose NETs in other locations.

8.5.2 Subtypes

A = persistent high AVP (e.g. pituitary / paraneoplastic)

B = reset osmostat (i.e. can still suppress AVP at lower POsm; commoner in elderly)

C = abnormal AVP response only a lower POsm

D = AVP undetectable (e.g. NSIAD or paraneoplastic AVP-like-peptide)

E = only recently described

…and some would consider cerebral salt-wasting (e.g. in SAH) as a distinct entity; others as a special instance of SIAD.

8.5.3 Treatment

Rationale for treating chronic, “asymptomatic” hypoNa is the biological plausibility and small-scale mechanistic studies that hypoNa may cause its associated morbidities: cognitive dysfunction, falls, fracture, death (Warren et al., 2023). For example, correction of PNa in an RCT was associated with improved biomarkers of bone formation. The evidence that ‘allostatic’ adaptation to hyponatraemia might cause various morbidities was reviewed by Portales-Castillo & Sterns (2019).

However, there is no guideline consensus or robust RCT evidence to support this approach. European Guidelines (2014) advise against treating mild, chronic, asymptomatic hypoNa (i.e. PNa > 130 mM) to raise PNa per se. A Cochrane review found that there is no high-quality evidence regarding the effects of correction of chronic, non-hypovolaemic, hypotonic hypoNa on hard patient outcomes.

First-line in all is fluid restriction:

- start c. 1000 ml per day and consider Furst ratio

- practically, can advise to ‘drink only when thirsty or eating’

Second-line options:

- tolvaptan (and ensure free fluid intake)

- urea (with fluid restriction)

- SGLT2i (+/- fluid restriction - e.g. 1500 ml in the JASN RCT)

- NaCl + furosemide (with fluid restriction)